Contributions of Muslims to the Field of Medicine

This article was produced and published by the Council of Islamic Education (CIE) that was founded in 1990. CIE is a national, non-profit research institute and resource organization based in Fountain Valley, California.

Please visit http://www.cie.org for more information.

In the field of medical knowledge, Muslim scientists had several sources on which to base their studies. The first source was Islamic teachings, including many religious requirements concerning hygiene. In addition, there is a saying attributed to Prophet Muhammad that for every disease, God has created a cure. The second source of learning was the body of Greek medical knowledge, developed by Hippocrates and Galen. These contributions were easily integrated into the study of Muslim medicine due to their focus on harmony and balance. A third source was the traditions practiced by Persians, Indians and others who practiced medicine at the teaching center of Jundi-Shapur (Iran). Both Jundi-Shapur and Baghdad had well-developed teaching Hospitals which attracted physicians from afar to study under famous teachers. Among the physicians who helped found the teaching hospital at Baghdad was the Bakhtishu family of doctors, non-Muslims who worked under the patronage of the Muslim rulers.

LINKS BETWEEN ISLAMIC BELIEF AND MEDICAL PRACTICE

An instrumental aspect of Islamic theology is the divinely ordained balance of life. This can be viewed through both a microcosmic window (looking at the smallest details) and a macrocosmic window (viewing the big picture of how all elements, up to the highest level are related). For instance, a scientist can look at a plant and recognize the vital, life-giving balance between the plant, the small living organisms which survive on the surface of the plant, and the fresh air which the plant needs in order to live. It is clear that the plant is part of a relationship that re-cycles elements that make up the fresh air, sunlight for photosynthesis, and the nourishment of the soil and the water. If just one of these elements is missing, the whole plant would cease to exist.

On a higher level, Muslims point to the relationship between the divine world (including angelic beings) and the physical world which is inhabited by people. It focuses on the human need to transcend the physical world and reach for a higher plane where one can obtain a purer state of existence in which one can understand the origin and principle of the universe. This field, sometimes called Islamic Cosmology, draws upon the wisdom of Qur’anic revelation, Hadith (sayings of the Prophet Muhammad), universal symbolism, philosophical descriptions of the cosmos, the ancient symbolism of numbers, and traditional astronomy (12).

THE ISLAMIC SOURCES

When looking at the practice of Muslim medicine, one must keep in mind that it is considered a Prophetic Medicine, based on a divine message passed down to humankind through the Prophet Muhammad. There are many Qur’anic verses which point to the elements of a healthy, well-balanced world as a sign of Allah’s mercy, power, and majesty. The Hadith (sayings of the Prophet Muhammad) and Shariah (Islamic Law) were important sources of Islamic medical practice:

“According to al-Tirmidhi, the Prophet said: He who wakes up in the morning healthy in body and sound in soul and whose daily bread is assured, he is as one that possesses the world.”

Al-Nasa’i relates that the Prophet said: “Ask God for forgiveness and health. After the security of faith, nothing better is given to a man than good health.”

The sayings of the Prophet Muhammad, as well as Islamic Law, served as guides to Muslim physicians. There are many collections of the traditional sayings of the Prophet Muhammad on the subject of medicine. These volumes link all three major sources of Muslim medicine into a whole, made up of elements of Qur’anic revelation, Prophetic traditions, and the Shariah, or Islamic Law. Muslim religious law gives a great deal of guidance in the field of personal hygiene. The simplest example is the fact that Muslims must perform ablutions (cleansing) before prayer in order to approach prayer in a physically as well as spiritually pure state. This is done at least five times per day. Brushing teeth at least daily is recommended. Regular bathing of the whole body, at least once per week, and the wearing of clean clothes ensured a high standard of personal hygiene even for the poor.

Muslim scholars prepared extensive and detailed books which served as guides to physicians who wished to treat their patients in a manner which remained within the parameters of Islamic practices and law. One of the more influential of these books is the Tibb al-Nabi, or “Medicine of the Prophet” by Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti. Al- Suyuti was born in Egypt in 1445 CE. Showing brilliance even as a child, he had memorized the entire Qur’an by the age of eight. Fortunately for modern scholars and physicians, he was a prolific writer and accomplished the important task of summarizing several centuries of scholarship concerning recorded Hadith which deal with the issue of health care. His book is divided into three distinct sections and offers a wealth of information about the medieval treatment of illnesses. In his opening passage, parts of which follow, al-Suyuti clearly presents the link between religion and health care:

“In the name of God, the Beneficent, the Merciful. Praise be to God who has given existence to every soul and has inspired each towards good acts and bad acts, and has taught what is for their good, what is for their harm, what causes sickness and what causes health, and has given death and bestowed new life.. It is obligatory upon every Muslim that he draw as close to the Almighty God as he can and that he put forth all his powers in attention to His commands and obedience to Him and that he makes the best use of his means and that he succeeds in drawing near to Him by conforming to what is commanded and refraining from what is forbidden and that he strives for what gives benefit to Mankind by the preservation of good health and the treatment of disease. For good health is essential for the performance of religious obligations and for the worship of God” (13)

Because it was a religious obligation to take care of one’s health, Muslim physician-scholars, referred to as Hakeems, were influential and valued citizens throughout the Muslim lands. These Hakeems passed on to others the great wealth of medical knowledge which the Muslims were developing with the help, in particular, of Christian and Jewish physicians. Great medical schools were attached to hospitals throughout the Muslim lands at cities such as Jundi-Shapur in Persia, Baghdad, Damascus, Cairo, and Cordoba. Supported by religious endowments called waqfs, the teaching hospital became the focus of scientific research in Muslim lands. Waqfs also supported the construction and upkeep of public baths and municipal drinking fountains, indicating an early understanding of the vital link between personal hygiene, clean drinking water, and physical well being. Many of these fountains and baths, called hammams, were so critical to medieval Muslims that they were constructed with the intent to provide centuries of service to the populace. When medieval writers described Islamic cities, a critical element of their narration was an indication of the number of masjids (mosques), libraries, fountains and public baths in a given city. For example, hammams numbered in the hundreds in Baghdad and other urban centers. Though some of the other buildings may have crumbled with time, well-maintained baths and fountains which are several centuries old still stand in cities such as Fez, Damascus, Tehran, Istanbul, and Cairo.

THE THEORY OF MUSLIM MEDICINE

Muslim physicians saw the human body as an extension of the soul. Like those who practiced traditional medicine in cultures such as those of India and China, Muslims also believed that there was a clear link between cosmic forces and the well being of humans. This natural and delicate balance between all created things forms the basis of traditional Islamic medicine. This view assumes that good health is the natural state, and illness is the result of an imbalance. Using the language and concepts developed by the Greeks, Muslim scholars expanded upon the idea that a person who had become ill had lost the delicate balance between the good humours and the bad humours. It was thought that with the restoration of this critical harmony, the illness would disappear, and good health would return.

Greek theory held that a healthful human body is based upon the complex balance and harmony of the following: the four humours, that is, blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile; the four natures of hot, dry, cold and humid; and the four elements of earth, water, air and fire (14). These concepts – widely prevalent at the time – were integrated into Muslim medical studies. It was believed that each individual had their own temperament, based upon either the balance or imbalance of all these elements. Diseases were associated with certain humours, so that if one were suffering from a disease which affected the yellow bile, which is hot and humid, they were to be treated with things which are dry and cold, such as certain foods, herbs, and medications. Al-Suyuti explains these elements in his Tibb al- Nabi:

“The Constitution of Man is concerned with seven components. The first component is the Elements which are four in number – fire, which is hot and dry, air which is hot and wet, water which is cold and wet, and earth which is cold and dry.

The second component is the Temperaments which are nine in number. The first is an evenly balanced temperament. The second is an unevenly balanced temperament, which may be unmixed, being then hot, cold, damp, or dry. Or it may be an unevenly balanced but mixed temperament…

Next among the seven components of the Constitution come the Four Humours. Of these the most excellent is Blood, which is damp and hot. Its property is to feed the body. Next comes Phlegm and this is wet and cold. Its property is to convert blood whenever the body lacks food, to keep the organs damp and to prevent drying up due to movement. The third humour is Bile which is hot and dry. It is stored in the Gall Bladder. It renders the blood subtle and helps it to pass through the very narrow channels. Finally, there is the Spleen. This is cold and dry. It thickens the blood and feeds the spleen and the bone. Spleen is sometimes called Black Bile”. (15)

The importance of psychological health and its relationship to one’s physical well being was also understood by the Arabs as early as the 8th century. Concerning the psychological state of people, al-Suyuti wrote:

“The body is indeed changed by emotions. The emotions include: ANGER, JOY, APPREHENSION, SORROW, SHAME.”

People were advised by al-Suyuti to follow the Prophet Muhammad‘s example and turn to God for refuge when suffering from apprehension and sorrow. Centuries before al-Suyuti, the famous physician al-Razi (Rhazes in Latin) had written a book of essays on maintaining health, called Spiritual Healing. He advised moderation in food and drink, and avoiding anxiety, anger, and excessive behaviors of all kinds. In an effort to improve the psychological condition of patients, the famous 10th-century Adudi hospital in Baghdad offered soothing music, poetry and the sound of running water to calm people down and speed recovery. In an early form of Social Services, patients also received a small sum of money upon their release from the hospital in order to facilitate a smooth transition back into the community. The poor were treated free, and gardens were available, not just for growing fresh herbs for the hospital pharmacy, but also for the recreation and refreshment of recovering patients.

A COMBINATION OF TREATMENTS

Muslim physicians treated their patients with a combination of diet management, medication, isolation of contagious diseases, prayer, fresh air, healing scents, and reduction of psychological stress.

“O ye who believe! Eat of the good things that We have provided for you. And be grateful to Allah, if it is Him that you worship.” (Qur’an 2:172)

Because many foods such as pomegranates, lentils and olives are specifically mentioned in the Qur’an, diet was a particularly critical element of a patient’s treatment. Again, physicians drew upon the wisdom of the Prophet. Al-Suyuti’s Medicine of the Prophet lists page after page of descriptions of the medicinal properties of specific foods. For example, limes are said to be hot and dry within the peel and the seed, but the leaf is considered cold: therefore, the leaf should be administered to a person with problems of heat-related illnesses of the blood and yellow bile. Limes were used to cut phlegm, destroy bile, and reduce vomiting. The healing and calming qualities of floral and wood scents were also listed, such as violet and sandalwood to reduce headache, and frankincense to fumigate the air of homes.

THE INFLUENCE OF MUSLIM MEDICAL THEORIES ON EUROPEAN PRACTICE

Physicians in medieval Europe also adopted from the East the concept that people had certain humours or personality types, and that these humours could offer physician clues about diet and the treatment of illness. The disease was thought to be the result of an excess of heat, cold, dryness or humidity. The patient’s diet was usually the focus of treatment. As in many other cultures, the links between the four humours, four elements, and the four natures as well as the zodiac are clearly depicted in medieval European manuscripts, art and folklore. This was the prevailing paradigm, or explanatory model, of the age.

The good health diet was supposed to maintain a proper mix of humours suited to the temperament of the individual. But initially, treatment was rendered in the complete opposite way than the Arab physicians would have proceeded. European physicians believed that those who were warm by nature, were naturally attracted to hot foods, and hence, in contrast to what the Arabs would have suggested, we're encouraged to follow their desires and eat hot foods when feeling ill. (Arab physicians would have suggested eating cold foods, to restore the patient’s balance.) Europeans were following the advice offered in the book Regime of the Body, written in the 13th century by Aldebrandino of Sienna. This practice continued to be the dominant method of treatment in Europe up to the 16th century.

HEALING THROUGH A COMBINATION OF RELIGIOUS FAITH, FOLK TRADITION, AND SUPERSTITION

In describing links between Christian theology and the study of medicine, Grollier’s The History of Medicine makes the following statement:

“During the Middle Ages, the influence of Christian theology affected medicine in several ways. The Christian emphasis on charity and concern for the sick and injured led to the establishment of hospitals often related to and maintained by monastic orders. In the later Middle Ages, spacious, fine hospitals were built by the Knights of St. John, including Saint Bartholomew’s in London and one at Rhodes. The concern of Christian theology, on the other hand, was to cure the soul rather than the body; the disease usually was considered supernatural in origin and cured by religious means. As a result, scientific investigation was inhibited during this time. Brothers of various monasteries copied and preserved those scientific manuscripts and documents which were thought to be consistent with prevailing religious thought, notably the works of Galen and Aristotle.” (16)

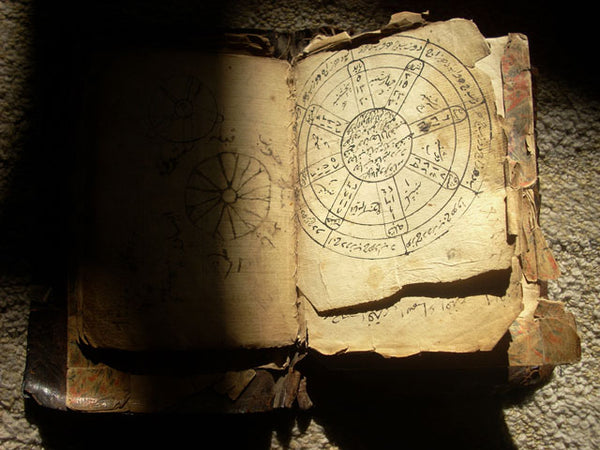

Both Arab and European cultures have strong folk traditions of using superstition, magic, astrology, and amulets to cure ills. Even with all their advances in the field of medicine Muslim physicians, like their European counterparts, continued to turn occasionally to these folk traditions as healing aids. For instance, Islam developed in a region where people believed that they could be struck by the “Evil Eye“. (This belief developed in pre-Islamic Arabia during the era Muslims refer to as the “Time of Ignorance”.) This tradition continued after the rise of Islam, and is prominently dealt with in al-Suyuti’s Medicine of the Prophet where the following advice is offered:

“If anyone of you is struck by the Evil Eye and asks for water in order to perform ablution (ritual cleaning) then his request should be granted. And he who is struck by the Evil Eye will wash his face, his hands, his elbows and knees, and the tips of his feet, and what lies within his breeches. He will collect this water in a cup and pour it over the possessor of the Evil Eye. He will turn the cup upside down behind him on the ground. It is said this pouring upon him will bury the effects and he will be cured by the permission of Almighty God. So it is said by the Imam Malik in his al- Muwatta.” (17)

Although their religious validity was strongly debated among Muslims, astrology, numerology (belief in magical qualities of numbers), charms and amulets also continued to be used in medieval times to protect one from evil and illness. During the time of the Black Plague in particular (which reached its peak in the mid-1300s), Christian and Muslim population centers were so devastated by the disease that people turned to every available cure possible. They sought refuge in both superstition and in their religion, often making little distinction between the two. Wealthy Christians carried on their bodies small vials of glass which held what were thought to be the tears of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Some carried relics, such as a bone or piece of hair of a saint, which they purchased on a religious pilgrimage. Poor people had to make do with the bone of a frog’s head or the tongue of a poisonous snake. Another sure remedy was to wait until the stomach was empty and eat a piece of paper inscribed with prayer and folded seven times. (18)

Muslims frequently wore amulets and rings which had Arabic letters inscribed on them. These letters were thought to have protective qualities because the Qur’an, which is considered the literal, unchanged word of God, was handed down to mankind in Arabic. Qur’anic passages such as those below indicated to the devout that wearing letters or carrying written verses of the Qur’an in their clothing would safeguard people from the plague:

“We sent down (stage by stage) of the Qur’an that which is a healing and a mercy to those who believe…” (17:82)

“Say: It (the Qur’an) is a guide and a healing to those who believe.” (41:44)

“We have sent it down as an Arabic Qur’an in order that ye may learn wisdom.” (12:2)

THE EXCHANGE OF IDEAS

The two greatest times of rapid exchange of medical knowledge between the Islamic Empire and Latin Christendom took place during the Crusades (11th-13th centuries) and the Black Plague (14th century). We can learn much about the exchange of medical information by studying the writings of those people who wrote chronicles describing their experiences. One of the most famous essays written about the differences between European and Arab treatment of the sick and wounded in the following chronicle written by Usamah Ibn Munqidh, a prominent Syrian Muslim who wrote during the time of the Crusades. (It is interesting to note that Usamah’s story relates the experience of a highly respected Christian physician who was practicing medicine among the elite Muslims of Syria at that time.):

One day, the Frankish (French) governor of Munaytra, in the Lebanese mountains, wrote to my uncle the sultan, asking him to send a physician to treat several urgent cases. My uncle selected one of our Christian doctors, a man named Thabit. He was gone for just a few days, and then returned home. We were all very curious to know how he had been able to cure the patients so quickly, and we besieged him with questions. Thabit answered:

“They brought before me a knight who had an abscess on his leg and a woman suffering from consumption (excessive fatigue and general poor health). I made a plaster for the knight, and the swelling opened and improved. For the woman, I prescribed a diet to revive her constitution. But a Frankish doctor then arrived and objected, ‘This man does not know how to care for them.’ And, addressing the knight, he asked him, ‘Which do you prefer, to live with one leg or die with two?’ When the patient answered that he preferred to live with just one leg, the physician ordered, ‘Bring me a strong knight with a well-sharpened battle axe.’ The knight and the axe soon arrived. The Frankish doctor placed the man’s leg on a chopping block, telling the new arrival, ‘Strike a sharp blow to cut cleanly.’ Before my very eyes, the man struck an initial blow, but then, since the leg was still attached, he struck a second time. The marrow of the leg spurted out and the wounded man died that very instant. As for the woman, the Frankish doctor examined her and said, ‘She has a demon in her head who has fallen in love with her. Cut her hair.’ They cut her hair. The woman then began to eat their food again, with its garlic and mustard, which aggravated the consumption. Their doctor affirmed, ‘The devil himself must have entered her head.’ Then, grasping a razor, he cut an incision in the shape of a cross, exposed the bone of the skull, and rubbed it with salt. The woman expired on the spot. I then asked, ‘Have you any further need of me?’ They said ‘No’, and I returned home, having learned much that I had never known about the medicine of the Franj (French).” (19)

SPECIFIC CONTRIBUTIONS OF ISLAMIC MEDICINE (20)

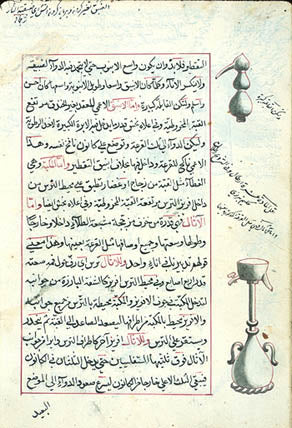

By the late 16th and early 17th century, European medicine had begun to adopt a different treatment of disease from the earlier European traditions. They relied on encyclopedic works like the Canon of Medicine by Ibn Sina (Avicenna) and the Book of Mansur, al-Razi’s major work under the Khalifah’s patronage. These works described diseases and treatments systematically and thoroughly, in a scientific manner that still holds up even today. Differential diagnosis, testing of cures, and carefully recorded clinical results were hallmarks of the works of these two giants of science whose place in history has been universally recognized. These and a large number of other works, including Al-Zahrawi’s Encyclopedia of Surgery and Instruments, and pharmacology encyclopedias by numerous authors, as well as translations of the best Greek works, such as those of Galen, had all appeared in print by 1500 CE. Of the hundred or so known Muslim scientific works printed in the first century of printing, about 30 of them were on the topic of medicine. They were standard textbooks in all the universities through the 17th and 18th centuries.

Europeans adopted the Islamic medical theory that people should be treated with a diet that restores the natural balance. In other words, people should be restored to equilibrium through food and medicine rather than indulged in their cravings and desires. The Tresor de Sante, written in 1607, maintained that foods and drinks that are humid and warm in quality should be given to those of melancholy humour (that is, dry and cold). Warm and dry foods should be given to those of a phlegmatic (cold and humid) nature, and so on. (21)

The development of medical sciences within the broad Islamic world led to great advances which influenced European healthcare for centuries. Following is a partial list of medical advances made by scholars working within the Muslim realm:

Translation and Transmission of Medical Knowledge

Arab scholars translated Greek, Persian and Indian texts into Arabic. After making corrections and commentaries and adding new discoveries, these books were later translated into Latin and passed on to Europe where they served as the major texts for European medical schools. Arabs saw the links between diet, psychology, a healthy lifestyle and human wellness. They established “teaching hospitals” which served as a prototype of today’s hospitals that contain medical schools, libraries, pharmacies, and laboratories. The basic foundations of the field of Pharmacology were formed.

The Philosophy and Theory of Medicine

Hunayn ibn Ishaq (809-873), director of Baghdad‘s House of Wisdom, wrote the al-Masa’il fi al-Tibb (“Introduction to the Healing Arts”) which was later translated into Latin as the Vade Mecum of Johannitius. This book, and others like it, influenced theories of medical care in Latin Christendom. He is also the author of an anatomical and detailed study of the eye, among many other works.

Clinical Medicine

Scholars in the Muslim tradition made advances in diagnosing and treating smallpox, measles, eye diseases, skin diseases, and other ailments. Advances were made in nutrition, mother and childcare and the use of drugs to cure illness. They also wrote about the effects of the environment on health. It was Muslim physicians who realized that diseases are contagious and hence, should be isolated within specific hospital wards. They set the standards for medical experimentation and clinical observation. Ibn Sina (980-1037), known as Avicenna in the West, wrote the monumental Canon of Medicine which listed every known disease of the time as well as its cure. This publication served as the major medical school textbook in European universities well past the Renaissance.

Ophthalmology

Due to the hot, dusty setting of the Middle East, medieval Islamic medical records reflect a high incidence of eye diseases such as trachoma and opthalmia. The Arab advances in eye care were not surpassed until the 17th century. Studies were conducted on the anatomy of the eye, the brain and the optic nerve, bringing a clear understanding of the elements of vision. (Until this time, scientists believed that vision was caused by rays which were sent out of the eye, instead of understanding that sight is the result of light rays going into the eye and being directed by optic nerves to the brain.) Muslim eye surgeons were able to remove cataracts by use of a hollow needle and suction, a procedure which was revived in 1846 by a French doctor.

Surgery, Anatomy, and Physiology

Arab physicians had a clear understanding of the pulmonary circulatory system, discovering the lesser circulation of the blood and smaller vessels. They also described the four chambers of the heart and explained the working of heart valves and how they kept blood flowing in one direction. They invented sedatives and narcotic drugs which enabled them to perform surgery, for which they invented over 200 instruments. Sutures (stitches) were made of animal intestines and silk. Antiseptics such as alcohol (from the Arabic word al-kohl) enabled surgeons to reduce the risk of infection.

Pharmacy and Pharmacology

This field became a separate science for the first time in history under the leadership of people such as Sabur bin Sahl (died 869) who wrote the earliest known book of medicinal recipes in Islam. Drugs, herbs, and spices from Africa to China were categorized and studied in a scientific manner. Case histories were written to track the success of treatments. Due to the religious belief that Allah has created a natural cure for every disease, scientists within the Islamic empire focused their studies on the use of natural remedies. For this reason, many hospitals had herb gardens adjacent to them, and pharmacies for mixing fresh and potent remedies. Among the other important scientific advances that aided pharmacology were horticulture, or the science of gardening, and chemistry, which aided in the discovery and preparation of natural substances. Chemists discovered ways to purify, isolate, and concentrate these substances. Muslim pharmacists also gave the world syrup-based medicines that made them easier to take, as well as ointments, compounds, essences, and tinctures. One contribution that is particularly useful for modern-day hikers is a medicine for insect bites – calamine lotion – which takes its name from the Arabic word for zinc.

Sources:

12. Nasr, Islamic Science, An Illustrated Study, (Westerham, Kent: World of Islam Festival Publishing Company Ltd., 1976), p. 31.

13. Cyril Elgood, transl., Tibb ul-Nabbi of Al-Suyuti, The Medicine of the Prophet, by al-Suyuti. (Cooksville, Tennessee: Tennessee Polytechnical Institute, n.d.), p. 48.

14. Nasr, Islamic Science, An Illustrated Study, p. 160.

15. Elgood, pp. 49-50.

16. Grollier 1995 Electronic Encyclopedia, ‘The History of Medicine.’

17. Elgood, pp. 63-64.

18. E.R. Chamberlain, Everyday Life in Renaissance Times, (New York: Capricorn Books, 1967), p. 133.

19. Amin Maalouf, The Crusades Through Arab Eyes, (New York: Schocken Books, 1984), pp. 131-132.

20. Section adapted from John Hayes, The Genius of Arab Civilization, Source of Renaissance, (Cambridge MA: The MIT Press, 1983), pp. 173-186.

21. Philippe Aries and Georges Duby, A History of Private Life, Passions of the Renaissance, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1989), pp. 294-295.

The second image used in this article is taken from Islamic Medical Manuscripts at the National Library of Medicine, go to http://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/arabic/catalog_tb.html

Leave a comment

Also in SCIENCE & MEDICINE

Revolution by the Ream

Paper, one of the most ubiquitous materials in modern life, was invented in China more than 2000 years ago. Nearly a millennium passed, however, before Europeans first used it, and they only began to manufacture it in the 11th and 12th centuries, after Muslims had established the first paper mills in Spain. The German Ulman Stromer, who had seen paper mills in Italy, built the first one north of the Alps at Nuremberg in the late 14th century.

The cultural revolution begun by Johann Gutenberg's printing press in 15th-century Mainz could not have taken place without paper mills like Stromer's, for even the earliest printing presses produced books at many times the speed of hand copyists, and had to be fed with reams and reams of paper. Our demand for paper has never been satisfied since, for we constantly develop new uses for this versatile material and new sources for the fiber from which it is made. Even today, despite the computer's promise to provide us with "paperless offices," we all use more paper than ever before, not only for communication but also for wrapping, filtering, construction and hundreds of other purposes.

Scientific Inventions by Muslims

Inventions

Abul Hasan is distinguished as the inventor of the Telescope, which he described to be a Tube, to the extremities of which were attached diopters”.

The Great Explorers of Islam

It was an Arab caravan which brought Hazrat Yusuf (Prophet Joseph) to Egypt. Moreover, the fertile areas in Arabia including Yemen, Yamama, Oman, Bahrein and Hadari-Maut were situated on the coast, and the Arabs being sea-faring people took sea routes in order to reach these places and fulfilling their commercial ventures.