2e Édition De Fikra “la Créativité Est Le Pilier De L’entrepreneuriat”

Vincenzo Nesci, l’un des principaux promoteurs de la 2e édition Fikra, lors de cette conférence internationale a abordé «la création d’entreprise et l’entrepreneuriat». Selon le directeur exécutif de Djezzy, ces derniers, «doivent être réalisés dans des conditions d’optimisme et de créativité pour permettre un réel essor dans les domaines commercial, industriel et créatif»

Beit Al Qur’an - Religion, Art, Scholarship

The museum was founded by Dr. Abdul Latif Jassim Kanoo, a member of a Bahraini merchant family whose written history goes back more than a century. But part of the money to build it also came from donations collected in a public fund drive, the first attempted in an Arabian Gulf country. It was "an undertaking fraught with uncertainty," says Kanoo, but successful. Beit Al Qur'an carries out all the functions of a modern museum: presentation of permanent and visiting exhibitions, conservation and restoration of manuscripts, publication of books, research, and sponsorship of cultural activities, lectures and seminars.

Towers of Islam

For fourteen hundred years the Muslim faithful have heard the call to prayer—"this perfect summons"—issue from the air around them. First it came from a low rooftop a few steps from the simple dwelling of Muhammad, the Prophet, in Medina. Then the sonorous Arabic cadences began to fall from a variety of towers, each of which reflected in its line and proportion the art of those distant places drawn into religious accord by the spread of Islam. Five times each day—at dawn, at midday, in the late afternoon, just after sunset, and during the evening—the voice of the muezzin speaks to four hundred million followers of the message of God brought to the world by the Prophet, calling from the minaret, enjoining the faithful to their duty.

From spare mud towers and roofs in poor villages, and from soaring towers of such magnitude and ornament that men come from half a world away to stand before them enchanted, the holy call is breathed upon the air, and its sinewy cantillation stirs the devout heart in the most labyrinthine byway. Whether it is round, square, polygonal, or a combination of these forms; whether it has only a rude porch or an imposing gallery; whether it is plain or ornate, the minaret is the symbol of Islam.

The Geometry of the Spirit

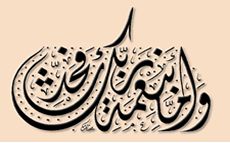

Islamic calligraphy is without doubt the most original contribution of Islam to the visual arts, yet it is only recently that it has come to be appreciated in the West. Even among lovers of Islamic art, calligraphy has been the interest of a minority rather than the majority. But in past years exhibitions of Islamic art have included more and more examples of calligraphy, and there have been successful exhibitions devoted entirely to calligraphy, such as that at Asia House, New York, in 1979 and the exhibition of the Musée d'Art in Geneva, which toured Europe in 1988 and 1989 and is now on display in Amman.

For Muslim calligraphers, the act of writing - particularly the act of writing the Qur'an or any portion of it - was primarily a religious experience rather than an esthetic one. Most Westerners, on the other hand, can appreciate only the line, form, flow and shape of the words that appear before them. Nevertheless, many recognize that what they see is more than a display of skill with a reed dipped in ink: Calligraphy is the geometry of the spirit.

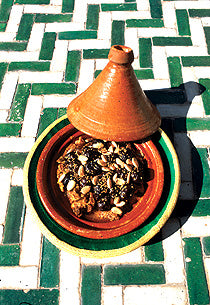

The Flavors of Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula has been closely linked with spices throughout its history. Spices were appreciated everywhere in the Middle East for their fragrances and their medicinal properties, as well as for their enhancement of flavor in food. Herodotus, "the father of history," wrote in the fifth century BC of the spices of Arabia that "the whole country is scented with them, and exhales an odor marvelously sweet." For centuries the Roman Empire, with its insatiable demand for Eastern spices, kept caravans crisscrossing the Peninsula, bringing such important spices as pepper, cardamom, cinnamon, ginger, spikenard, nutmeg and cloves to the West. Muhammad himself, as a young man before the Koran was revealed to him, accompanied caravans across the Peninsula to Syria, carrying goods which very likely included spices. After Islam was established believers came to Makkah from all over the world to make the Hajj, or pilgrimage, and enriched the Peninsula with an enormously varied culinary acquaintance. Arabian cooks developed a mastery of flavoring, using a multitude of spices in each dish to create a taste which is rich and subtle, never overpowering but magnificently enhancing the food.

The Fabric of Tradition

From classical times, nearly 3,000 years ago, through the golden ages of the Umayyad and Abbasid empires, the Arabian Peninsula was near the center of the Old World's stage. Two natural resources, frankincense and myrhh, tree resins from the southern desert mountains, were much prized in the empires of Greece and Rome. Somewhat like petroleum today, they were the basis of a number of popular commodities, and – again like petroleum – they brought the Peninsula into commercial contact with the rest of the world then known. They also, for a time, brought great wealth.

Later, after the resin market had collapsed, Arab seamen boldly sailed the monsoon winds to supplant the long-established overland caravan trade network and channel the goods of East Africa and the luxuries of Southeast Asia and the Far East through Arabia's market centers to medieval Europe. The powerful trade monopoly that resulted brought fabulous textiles, perfumes and jewels to the tribes and townspeople of the Peninsula.

A Treasury of Traditional Wisdom

One who praises you for qualities you lack, will next be found blaming you for faults not yours. – Ali Ibn Abi Talib (r.a.)

The true saint goes in and out amongst the people and eats and sleeps with them and buys and sells in the market and marries and takes part in social intercourse, and never forgets God for a single moment. – Abu Sa’id ibn Abi I-Khayr

Actions will be judged according to intentions. – Prophet Muhammad (PBUH)

Stumbling is the fruit of haste. – Ali Ibn Abi Talib (r.a.)

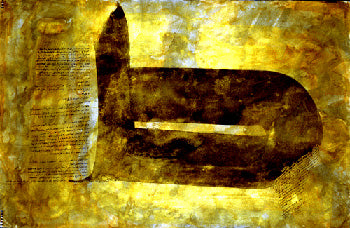

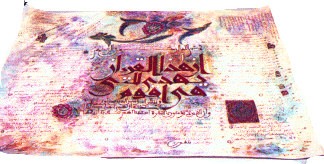

Letter, Word, Art

Across-section of such art, from the collection of the Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts, is on display at the Chicago Cultural Center through May 18, following a successful three-month exhibition at Agnes Scott College in Atlanta. It includes Osman Waqialla's strong, stylized letters in a wash of reds and ochres (1); Husain's fluid hand, which transforms "Huwwallah" ("He is God") into the outline of a boat upon the sea (12); busy, illegible swarms of words in works by Yussef Ahmad (8) and Mehdi Qotb; a single letter crafted by Ali Omar Ermes with one sure stroke of his thick brush (2) ; the interlocking Kufic script in Amin Gulgee's sculptures (19); and the illusion of depth Ahmed Moustafa creates solely with calligraphy (15).

Reflections of Benares Silk

The images featured in this article were taken by Ali Omar Ermes showing fine examples of Malaysian and Indian Silk.

Silk, a material which conjures up elegance; to see sensitive hands at work on it is to witness an act of sheer beauty. When minds and hands work together in a seemingly effortless way as they do during the transformative stages silk undergoes – from its raw state when it is taken from the cocoon of the mulberry leaf fed silkworm through the stages of carding, spinning, weaving and dyeing – until it is finally a piece of cloth, the effect is stunning. The end result of this co-operative endeavour is a material at once strong while remaining lustrous and delicate.

Upon asking about this craft in Benares, I was told that its production has rested from time immemorial with the Muslims, being produced not by a sole individual but rather as a joyous communal expression of diverse skills blending together.

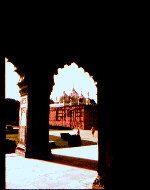

Sight – Sound – Scent – Shade

Since the time of the Prophet, Muslim gardeners have attempted to create an earthly paradise to praise God and please man’s senses. The Quran presents some wonderful images of gardens with beautiful trees and running streams to celebrate the magnificence of the Creator. In the afterlife, one of the rewards of the faithful is to rest in these gardens of Paradise, so it is hardly surprising that gardens have long been a favourite occupation throughout the Muslim world.

The art of the garden has developed over the centuries. The basis form of the garden in Muslim Middle East evolved in remote antiquity and was largely dictated by the land and climate. Heat, difficult soil and a scarcity of water ruled out gardens of the kind later favoured by the English, while the formal continental style would have been unbearably hot.

The World of Islam – Its Art

As the Festival of Islam proves, the arts of Islam show a surprising unity through the ages and across the wide vistas of the Islamic world. Although there are certainly individual differences, and even exceptions, it is easy to recognize the common elements.

Essentially, Islamic art is abstract—an art of patterns, symmetrical, two-dimensional, repetitive and infinitely extendable. Even when natural forms are used they are so stylized as to be virtual abstractions. The arabesque, for example, is based on vegetal forms but has a logic of its own and does not seek to reproduce the logic of growing things. Pure geometry is a strong element of design, mixing the curvilinear with the rectilinear. Another important element is calligraphy—Arabic writing—usually a quotation from the Koran and often drawn or carved in such complex ways as to be almost illegible. Color is also important, although rarely used realistically. Illusion is not an aim; stone or wood, paint or ceramic is not intended to represent actual bodies or leaves or animal forms but only to suggest an ideal. Pushed to the periphery of Islamic art, and never used in a religious context, is representation of the human form.

Calligraphy - A Noble Art

In a broad sense, calligraphy is merely handwriting, a means of recording and transmitting information, sometimes clearly, sometimes not, but in most instances hastily and with little regard for its appearance. In the Arab world calligraphy is something more. It is an art—indeed the chief form of visual art—with a history, a gallery of great masters and hallowed traditions. It is an art of grace and elegance which inspires wonderment for its appearance alone.

What distinguishes calligraphy from ordinary handwriting is, quite simply, beauty. Handwriting may express ideas, even great ideas, but to the Arab it must express, too, the richer dimension of aesthetics. Calligraphy to the Arab is, as the Alexandrian philosopher Euclid expressed it, "a spiritual technique," flowing quite naturally from the influence of Islam.