How the Central Banks Can Accommodate Islamic Banks

Dr Gamal Attia, Saturday 1 September 1984

The following is an abridged version of a paper given by Dr Gamal Attia of Islamic Banking System, Luxembourg to the Islamic Banking Conference, London, September 1984.

The relationship between Islamic banks and central banks was, and still is, rather tense. Islamic banks started in the 1970s in Muslim countries which were dominated by conventional banking systems and governed by western-style banking laws. Commercial banks in these countries, as well as central banks could not accept the idea of a banking system not based on interest (riba). Islamic banks were refused authorisation to operate.

Responding to the pressure of public opinion, however, the only way was to promulgate special laws exempting Islamic banks from the existing banks rules and even from the control of the central banks. Some Islamic banks were set up under the patronage of governmental authorities, which were, by nature, far from the ordinary banking systems. Examples are the Ministry of Social Affairs for the Nassar Social Bank in Egypt and the relevant Ministry of Awkaf (Religious Endowments) for the Faisal Islamic Bank of Egypt and Bahrain Islamic Bank.

With the success of Islamic banks some rose within a few years to match the first rank of the well-established conventional banks. Consequently, the central banks were forced to ask the legislative authorities to put this “unwelcome guest” under its control.

The Islamic banks naturally resisted these efforts, being protected by their own laws. Each party’s attitudes were somewhat exaggerated, central banks insisting that Islamic banks should be within their control under the same conditions as other banks, and Islamic banks insisting on being under no control at all.

The Islamic banks proposed, as in alternative, that the International Association of Islamic Banks or universal Islamic banks (existing already, such as the Islamic Development Bank of Jeddah, or to be established in Cairo, Kuwait or Bahrain under the name of the Universal Islamic Bank) would perform some of the duties of central banks.

These proposals were not practical: the most such an institution could offer would be coordination and cooperation, and it would not cover any of the functions of central banks. Central banks pursued the subject, discussing it twice during the meetings of the central banks of Islamic countries, held under the auspices of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference. The direction of the discussions was steered towards promulgation of such laws organising Islamic banking or, at least, a change in banking laws to include a special section on Islamic banking activities – in both cases under the control of central banks.

First, I find it necessary for there to be control over the activities of Islamic banks in order to protect their depositors as well as for the regulation of all activities. I feel strongly that there is a need to establish a kind of self-control in the forum of internal regulations, control mechanisms, cooperation between Islamic banks in this respect and an exchange of experience among them – especially between the newly-established ones and the other ones, so that this control system may develop in a way suitable to the nature of Islamic banking and the environment in which it is implemented.

Second, my personal view is that there should be neither total exemption of Islamic banks from control, nor their complete submission to the same rules governing other banks. Instead there should be different regulations suitable to the nature of Islamic banking, implemented by the central banks.

How then can central banks accommodate Islamic banks? Consider deposits on the basis of profit and loss sharing instead of on the basis of pre-determined interest rates. Here I mean fixed deposits, not current accounts, which are guaranteed by Islamic banks as they are by conventional banks.

The fixed deposits, as such, are basically different in Islamic banks than in other banks, where the sum deposited, as well as the interest due on it, is guaranteed by banks:

The Islamic banks, neither the principal deposit, nor a pre-determined yield on it, are guaranteed, in theory, by the banks. In this way Islamic banks do not stand as an original party in the relationship with both depositors and users of funds, but performs, instead, the role of a proxy of depositors, vis-a-vis, the user of funds. This proxy has two kinds:

Firstly, a proxy including delegation from depositors to invest their deposits in any project, called General Deposits, where Islamic banks invest with numerous users of funds and consider all these General Deposits as one pool. Profits of the investments are placed in this pool and then re-distributed among depositors on the basis of a points product system (each amount multiplied by number of days), after deduction of management fees.

Second, the proxy where the delegation from depositors is specified to investment of deposits in particular projects after approval and acceptance of the risks involved. The profits of these projects are distributed among depositors after deduction of management fees of the bank. This is called in Islamic banking terminology “specified deposits”.

It is clear that in these two kinds of deposits and especially the second, the bank performs the function known in the banking terminology as the “fiduciary function”. It is also assumed that in both cases the depositor is aware of the risks to which his deposit is exposed. This principle of capital risk is an incentive for him to deposit his funds in this kind of account and avoid depositing them in the pre-determined interest system. The principle of autonomous free-will of the parties – where it is not contradictory to public order and public morale – is the suitable legal basis for allowing this kind of deposit.

The legal basis of the depositor’s share in the bank’s profit is the agreement of the bank’s shareholders (who are the only ones entitled to the bank’s profit) to surrender a part of their profit to depositors.

This legal analysis leads us to the problem of subjecting the yield, distributing among depositors, to taxes. It is known that the interest on deposits, paid by the conventional banks, is an expense, and is therefore deducted from income before arriving at the net profit, which is subject to taxes. The net, after taxes, and reserve are to be distributed as divided to the shareholders.

In the case of Islamic banks, the accounting follows the same trend. The yield distributed to depositors (as opposed to dividends distributed to shareholders) is considered an expense on the profits of the bank, to be deducted before arriving at the net profit, subject to taxes. The treatment of interest on deposits in conventional banks is normal, as both are returns on money. Consider the use of these funds:

Finance of economic activities of the bank’s clients

This is implemented by riba banks on the basis of lending at a pre-determined interest rate and by Islamic banks on the basis of profit and loss (PLS) sharing, Murabaha (cost plus margin of profit) leasing, and so forth.

The principle of finance on a PLS basis is alien to riba banking due to the risk of decrease in the amount advanced in case of loss.

Islamic banks became aware at an early stage of the danger of confining their activities to this principle, and they limit these either by internal regulation or to a percentage of the total of its resources. Some banks even limit them to a percentage of the share equity of the bank.

Therefore, the regulation of this activity is acceptable by Islamic banks in the same way as riba banks are limited by regulations in buying stocks and shares in other companies up to a percentage of its own equity share capital.

As for financing on a Murabaha basis, (cost plus margin of profit), it does not raise any question of the possibility, in principle, of the bank having title to a commodity. In fact, from a practical angle, the ownership of a commodity is transferred immediately after the bank obtains its title, to the next buyer. Therefore, the question of allowing the bank to obtain the title to the commodity is similar to allowing a bank, in the case of documentary letters of credit, to obtain documents representing goods to order of the bank, which transfers them by endorsement to the opener of the letter of credit.

Although the purposes, in the case of letters of credit, is to give the bank collateral on the goods, while the purposes in the case of Murabaha, is to confirm the role of the bank as buyer and seller of the goods, it is still a problem of an academic nature, subject to review from the Islamic legal point of view in order to simplify the formula, making it as near as possible to reality and to the intention of the contracting parties.

In connection with this problem, another arises in countries where Value Added Tax (VAT) exists on the sale of goods, or where there is a tax on the transfer of ownership of real estate or cars. The payment of this VAT by Islamic banks, then a repayment of the same by the client, is a king of duplication of taxes, which increases the cost of the goods to the client.

It is hoped that the tax authorities take into consideration the financing role of Islamic banks and exempt them from these taxes, as conventional banks are exempted when financing on an interest basis. The difference in formulae should not be a reason for a difference in tax treatment.

As for finance through leasing of real estate, equipment, machinery and modes of transport such as aeroplanes and ships, which became one of the activities allowed to conventional banks in most countries, it does not represent a special problem when practised by Islamic banks and should be treated in the same way as for other banks.

Finance of economic activities through subsidiary companies, affiliated to the bank

This is another way by which Islamic banks can invest their resources, by establishing subsidiary companies in different sectors of the economy.

The capital of these companies could be wholly owned by the bank or it can have a controlling share. Besides, the bank finances the working capital of these subsidiaries according to one or more of the formulae used to finance third parties. Conventional banks sometimes use this way when the symbolic capital of the subsidiary company is within the radio allowed to banks in buying shares, while the finance of working capital, which is a higher amount, is treated as a guaranteed loan with a pre-determined interest rate.

In spite of the fact that the symbolic capital of the subsidiary is not considered a guarantee for the risk of lending large amounts, the difference in legal entities allows the banking supervisory authorities in some countries to disregard this activity and consider it according to its appearance as a guaranteed loan in the opinion of the bank’s management.

Islamic banks do not differ here from other banks, except that they treat their subsidiary companies according to the above-mentioned formulae. It is always possible, if considered satisfactory to the banking supervisory authorities, to consider the finance advanced from the Islamic bank to the subsidiary company as an interest-free loan and the bank receives the profit only, in the form of dividends distributed from the subsidiary company to the bank.

It is also possible to make a holding company, owned by the bank, or a holding company of the whole group including the bank, an intermediary for the finance of these subsidiary companies, although this situation differs from country to country, according to the limits imposed by banking laws to loans advanced to subsidiary and sister companies.

Performing economic and commercial activity

Islamic banks are permitted by law to perform all commercial, industrial, agricultural, transport, storage, mutual insurance activities and so on.

Here it is preferable to set some limits on the performance by the Islamic banks of direct commercial activities, as this includes unfair competition with its clients, who entrust the bank with their commercial secrets when obtaining the documents of imported goods through letters of credit, opened by the bank. Therefore, the banks, as well as being professionals entrusted with secrets of their clients, such as auditors and lawyers, should not practise the same activity so as to avoid clash of interest.

This concerns the trading in manufactured goods such as cars and tinned food. It does not concern trading in international markets, in raw materials, commodities, grain, metals and so forth, where prices are fixed through offer and demand in world stock exchanges, far from banks’ local customers.

However, the observation which could be made in this respect is the possibility of an Islamic bank taking an open position in such commodity transactions and taking unnecessary risks, which are speculative rather than trading risks. I propose also to put limits on the activities of Islamic banks in this regard.

In general, it is preferable to let subsidiary companies perform these direct activities in order to allow the banks to concentrate on their main function in the field of finance.

I shall now consider some characteristics of the proposed regulation of Islamic banking.

Minimum capital and capital to deposits ratio

The capital in an Islamic bank is an essential guarantee to protect the deposits in the short and long term. It is, therefore, necessary to impose strict conditions by stipulating a minimum of capital for Islamic banks, which is higher than the minimum for other banks.

For the same reason, it is also necessary to be stricter in the ration between capital and deposits in Islamic banks: for example, if the minimum for other banks is $20m capital, it should be $30m for an Islamic bank. If the ratio in other banks, between capital and deposits is 10%, it should be 15% in an Islamic bank.

Reserves and provisions

Reserves and provisions in Islamic banks represent another guarantee to protect deposits. It is, therefore, necessary to increase the percentage of reserves and provisions in order to face the risks to which other banks are not usually exposed, or exposed to a lesser degree.

Consequently, it is proposed that the legal reserve for Islamic banks be 10% of the profit instead of the usual 5% and for the general reserve to be 20% of the profit instead of the usual 10%.

It is also proposed that the use of the general reserve be made easier so as to obviate where necessary, routine procedures and limitations. This would help ensure equilibrium in the distribution of dividends from one year to another. These two kinds of reserves are to be deducted from the shareholders’ profits.

As for provisions, it is proposed to include the following: dimunition in the value of fixed assets; dimunition in the value of investment; inflation and impact on investments; doubtful debts; foreign exchange variations; taxes under settlement; self-insurance.

These provisions are to be deducted from the different pools of investment, whether concerning depositors or shareholders, as the case may be.

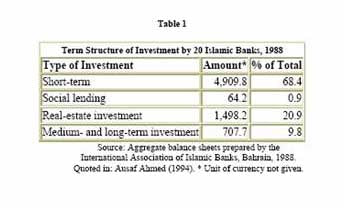

Liquidity ratios

The liquidity ratios required by banking laws, whether from current accounts or from total assets, differ from one country to another. In some countries the banking supervisory authorities reserve the right to impose different ratios on different banks according to their situation.

The operations of the conventional banks are based on lending at interest rates, which results in its assets becoming dues from third parties, with the possibility of being made liquid according to their nature, period and guarantees. Since Islamic banks are not based on the same principle, but are investing in assets, represented by commodities, shares in companies or working capital of companies, the possibility of these assets becoming liquid, if the need arises, is much more difficult than in conventional banks. This fact requires special attention when fixing their liquidity ratios in each kind of deposit and of each investment in order to allow a degree of liquidity higher than conventional banks.

Elements of liquidity reserve

Most banking laws require that the banks keep a part of the liquidity they are required to maintain in the form of deposits, (with or without interest), treasury bonds or bonds of specified qualities, with the central bank.

As Islamic banks are not operating on an interest basis, it is necessary, while applying the restricted requirements of liquidity, to allow the liquidity reserve required from them to be composed of elements in which Islamic banks are dealing, such as trade bills, shares and participating certificates of deposits, provided that it is negotiable according to special criteria.

Ratios of allowed risks

The basic idea of banking laws for protection of deposits is the minimisation of risk. Islamic banks do not contest this principle although it is widely known that the basic principle of Islamic banks in particular and Islamic economics generally, is the exposure to risk. This is not precisely the case and therefore needs some details and precision.

The rule has been established by many religious texts:

– The yield (return) is commensurate with the risk undertaken.

– Profit is justified on the basis of a likely loss.

– Yield (return) on capital not exposed to risk is not permissible.

It is evident that any income from an interest-based transaction, where capital and yield are totally secured, is prohibited because of the lack of risk element on the part of the owner of the capital.

On the other hand, betting and gambling, whether they result in gains or in losses (as is frequently the case), are prohibited operations because of the total risk involved. Between the two extremes of 100% security and 100% risk is located the area of allowed profit, carrying a portion of risk.

It is then up to the investor to choose the degree of risk he opts to expose himself to, and naturally, the higher the risk, the higher the profit and, on the contrary, the lower risk involved the lower the profit.

Consequently, the banking formulae known as “Security, Liquidity and Profitability” is also known in Islamic banking, though in different practical forms. Conventional banks took the principle of 100% security in their transactions, which can not be adopted by Islamic banks. The formula practised by Islamic banks, though different from conventional banks, should, in the end, lead to this formula being respected, which is the basis of success of banking activity.

If the formula proposed by Islamic banks is, prima facie, a deviation from criteria of security in contemporary banking concept, we should refer, here, to two main points:

– The restrictions proposed on the capital, the ratio of capital to deposits, the percentage of reserve and provisions and ratios of liquidity, are the security valves which compensate this relative deviation from the 100% security in the Islamic banking formula.

– The formula adopted by conventional banks to follow the 100% security did not prevent them from getting into difficulties, the least of which is bankruptcy of some banks, which happens from time to time. The real lesson we should learn from the dilemma of Third World debt is that depending on the creditor-debtor relationship not being the real expression of the 100% security principle, it could even lead to the total loss of capital and interest. The solution would lie in a formula where the security on the face is less than 100% but where the creditor participates in the management of the funds and shares of the results of its investments, carrying the real security for both capital and yield.

Proposed formula for allowed risk ratios

This is a formula to be reviewed in the light of practical experience, the basis of which is to distinguish between the funds of shareholders where a greater portion of risk could be allowed and the funds of depositors where it is necessary to minimise the risk. One can have two main pools:

– A pool of shareholders’ equity, the income of which comes from fees of banking services, dividend (profit) of capital invested and a share of the yield of deposits as management fees, and out of which the general expenses are deducted.

– A pool of depositors’ funds. This is proposed to be divided into different baskets according to currencies in order to allow the investment of deposits in the same currency and consequently avoid currency variation risks. It is also necessary to follow the matching principle between periods of deposits and periods of investments.

Supervision by depositors over Islamic banks activities

Since the depositors in an Islamic bank shares in its profit and loss, while the relationship of depositor to the conventional bank is one of debtor and creditor, it is recommended, while elaborating suitable systems for the activities of Islamic banks, to give depositors a kind of supervision over the activities of Islamic banks, which could take the form of a depositors’ General Assembly (similar to the bond holders’ General Assembly, allowed in some countries) entitled to participate in the discussions of investment accounts and to elect the auditors. Attending such a depositors’ General Assembly could be limited to those depositors who have a minimum of $100,000, for instance, and whose period of deposit is one year minimum.

This article featured in Arabia – The Islamic World Review, Nov 1984 – Volume 4, Number 39.

Leave a comment

Also in FINANCE & ECONOMICS

Recent History of Islamic Banking and Finance

Islamic Banking- an Analytical Essay

The Foundations of Islamic Finance

During the short span of a quarter century, a new way of financial intermediation and investment management emerged and gained a sizeable part of the market – between a fourth and a third – in its home base, the Persian Gulf countries. During the same period it spread far and wide reaching Malaysia and Indonesia in the east and the Americas in the west, and a number of Muslim countries adopted the new system at the state level.

It is interesting to ask why it emerged, how it works, what sustains it and what are its potentialities for you and me and the humanity at large. The query is timely as all is not well with our conventional system of money, banking and finance. It has become increasingly unstable, facing recurrent crises. It has failed to help in reducing the increasing gap between the rich and the poor, within nations and between nations. Many think it is partly responsible for increasing inequality.